A tutorial for getting started with particle physics research and ROOT.

- Install ROOT:

- Running ROOT:

- Looking inside a Data file

- Making quick plots from ROOT

- Analysis code with ROOT

- Finding the D meson

- Homework

Under "Latest ROOT Releases" download the latest "Pro" release, for this example 6.08/02 2016-12-02, https://root.cern.ch/content/release-60802 Ex: for Ubuntu: https://root.cern.ch/download/root_v6.08.02.Linux-ubuntu16-x86_64-gcc5.4.tar.gz

In linux, unzip the file you downloaded, ex:

gunzip root_v6.08.02.Linux-ubuntu16-x86_64-gcc5.4.tar.gz

tar -xvf root_v6.08.02.Linux-ubuntu16-x86_64-gcc5.4.tarNow you have a directory root, say it's in your home folder ~/root To use root we need to source a script to set some environment variables.

source ~/root/bin/thisroot.shAdd that line to your ~/.bashrc or ~/.bash_profile file so that it's always executed when you start the terminal and you can always use root.

To install ROOT on Windows you need to first install bash for Windows: http://www.howtogeek.com/249966/how-to-install-and-use-the-linux-bash-shell-on-windows-10/ , then you need to install the root prerequisites within bash,

sudo apt-get install git dpkg-dev cmake g++ gcc binutils libx11-dev libxpm-dev libxft-dev libxext-devThen install Xming and add export DISPLAY=:0 to your .bashrc file to see be able to see plots and graphics. After this the steps are the same as above for Ubuntu.

To run root just type root from the command line.

rootIf all goes well you should see a splash screen (which means display is working and you can see plots) and something like this:

------------------------------------------------------------

| Welcome to ROOT 6.08/02 http://root.cern.ch |

| (c) 1995-2016, The ROOT Team |

| Built for linuxx8664gcc |

| From tag v6-08-02, 2 December 2016 |

| Try '.help', '.demo', '.license', '.credits', '.quit'/'.q' |

------------------------------------------------------------

root [0]

This means root works and you can issue commands to the root interpreter line by line for it to run. This is useful for quickly looking at some data and checking if something is working, however for more serious analysis we'll be writing code that we compile and run. For now let's see a few things we can do from the root command prompt. First let's exit root by typing .q

root [0] .q

Before going to the next step clone this repository to your computer and we'll use it as our working directory since it has some settings inside which make nicer looking plots.

git clone https://github.com/velicanu/introduction.git

cd introductionLet's grab a sample input file of real collision data and open it in ROOT, and use this to go over some of the ways we can use the root interpreter.

wget http://web.mit.edu/mithig/samples/g.pp-photonHLTFilter-v0-HiForest-tutorial.root

root -l g.pp-photonHLTFilter-v0-HiForest-tutorial.rootNext we can type .ls to see something like this:

root [0]

Attaching file g.pp-photonHLTFilter-v0-HiForest-tutorial.root as _file0...

(TFile *) 0x2300530

root [1] .ls

TFile** g.pp-photonHLTFilter-v0-HiForest-tutorial.root

TFile* g.pp-photonHLTFilter-v0-HiForest-tutorial.root

KEY: TTree ztree; Jet track tree

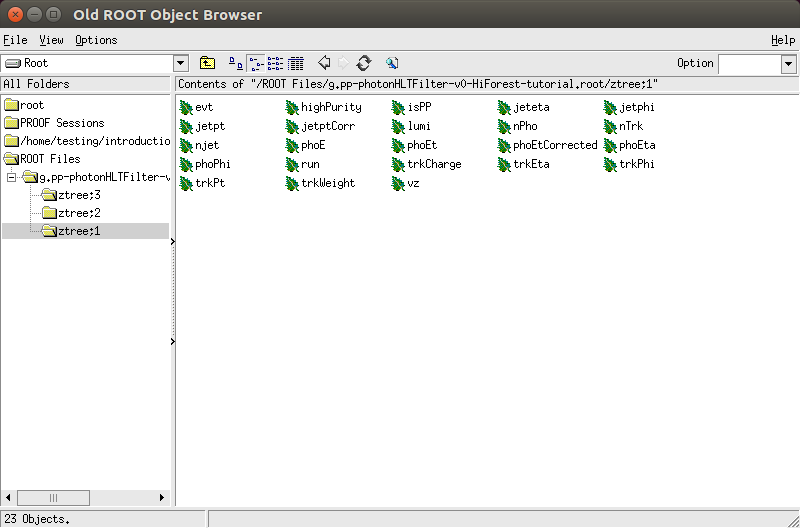

Here root is telling us it's opened the file, and inside it sees a TTree called ztree. We can open a TBrowser to see what's inside:

root [2] TBrowser b

Here we see the different leaf types inside the tree, which each stores some type of information about the event. While the specific leaves shown here are arbitrarily chosen and will vary from experiments and analyses, the same general concepts apply so let's go through some of them in detail to get a better understanding of what type of collision data there is and how it's stored.

Each collision will have some global properties that can be represented by a single number or boolean in the tree. Some examples of this are shown below:

isPP = type int , 0 if PbPb collision data, 1 if pp

run, event, lumi = a set of numbers describing when the event was recorded, the combination should be unique in data

vz = the z position of the collision along the beampipe, with 0 being the center of the detector

Many colliders, CMS included, detect charged particles with high precision by using a detector called a tracker, where the charged particles deposit energy in points as they traverse, and then algorithms reconstruct the trajectories of individual particles from these points and we can extract information like momentum and the charge of the particle by how it bends in a known magnetic field. We call these reconstructed trajectories tracks, and since there can be many charged particles produced in a single collision, we store the information about tracks as arrays indexed by which track we are looking at. The variables are described below:

nTrk = the total number of reconstructed charged particles, this is a single integer for each collision

trkPt[i] = the transverse momentum of the i'th particle

trkEta[i] = the pseudorapidity of the i'th particle, in CMS this ranges from -2.4 to 2.4

trkPhi[i] = the azimuthal angle of the i'th particle, from -pi/2 to pi/2

trkCharge[i] = the charge of the i'th particle, since we can only reconstruct charged particles this will be -1 or 1

trkWeight[i] = the correction factor to be applied to the i'th track to account for efficiency and mis-reconstruction

Photons are reconstructed using the electromagnetic calorimeter in the detector. Like charged particles, there can be multiple photons per collision so we store photon related variables as arrays as well.

nPho = the number of reconstructed photons, a single integer for each collision

phoE[i] = the energy of the i'th photon

phoEt[i] = the transverse energy of the i'th photon

phoEtCorrected[i] = the transverse energy of the i'th photon after applying some corrections

phoEta[i] = the pseudorapidity of the i'th photon

phoPhi[i] = the azimuthal angle of the i'th photon

Nature prevents quarks and gluons from existing in a deconfined state that reaches our detector, instead quarks and gluons with high enough momentum will produce lots of particles around themselves and appear in a detector as a collimated spray of particles, which we call a jet. Due to energy and momentum conservation we know that the sum of the total energy and momentum of all the particles in the jet must equal the initial energy and momentum of the quark or gluon the jet originated from. However we don't know for sure which particles are part of the jet and which aren't, so we rely on algorithms to both decide and define what is measured as a "jet" . While jets occur more rarely than charged particles, there can still be multiple jets per collision so we also store jet related variables in arrays.

njet = the number of reconstructed jets, a single integer for each collision

jetpt[i] = the transverse momentum of the i'th jet

jetptCorr[i] = the transverse momentum of the i'th jet after applying some corrections

jeteta[i] = the pseudorapidity of the i'th jet

jetphi[i] = the azimuthal angle of the i'th jet

While the names and types of variables you'll encounter in data will be different than these, the idea that certain variables describe a collision, and other variables describe objects within that collision is a general concept.

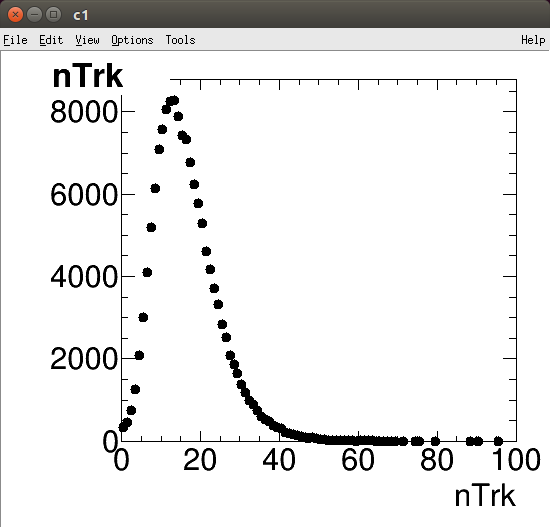

Open the file described above and the TBrowser until you get to the same image as shown above. If you just double click on the variable called nTrk you should see an image like the one below, this shows us the distribution of the number of charged particle per collision, for all collisions in the file that we opened. Try right clicking on the plot and changing the y-axis to log scale and discover what other tools are available to us for manipulating plots.

Next double click on the variable called trkPt and you should see a new plot appear. This plot will be the distribution of the transverse momentum of all reconstructed charged particles, in all collisions in our file. You'll notice that due to the tail of this distribution most points are close to either the X or Y axis. Suppose we want to take a closer look at the distribution of just particles having trkPt < 10 GeV only in events having at least 20 particles. To make this selection we go to the root command line and type the following:

root [3] ztree->Draw("trkPt","trkPt<10 && nTrk>20")

You should have seen something like this in the tutorial on the root website, but let's go over that this line does in detail. Recall when we did .ls , ROOT told us it sees a TTree called ztree.

root [1] .ls

TFile** g.pp-photonHLTFilter-v0-HiForest-tutorial.root

TFile* g.pp-photonHLTFilter-v0-HiForest-tutorial.root

KEY: TTree ztree; Jet track tree

In C++ terms ztree is a pointer of type TTree, and thus we can use all the functions a TTree has defined. You can see the full list of what TTree's can do here: https://root.cern.ch/doc/v608/classTTree.html . Usually google-ing the class name will lead you to the documentation, although the results surprise you from time to time like when you try to google for TAxis :)

So our command takes the TTree pointer ztree, and calls the Draw function with two parameters, the first being what we're drawing "trkPt" and the second being the cuts we are applying "trkPt<10 && nTrk>20" . In this case we are applying one cut on tracks, requiring their momentum to be greater than 10 GeV, and we're applying a second cut on collision events requiring they have more than 20. What should the command be if we want to see the azimuthal distribution of charged particles having less than 10 GeV of transverse momentum?

The ROOT command line can also show you both what functions a class has available and what parameters they expect as input by typing the ClassName::FunctionName( and pressing tab, for example below I pressed tab after typing TTree::Draw( :

root [8] TTree::Draw(

Long64_t Draw(const char* varexp, const TCut& selection, Option_t* option = "", Long64_t nentries = kMaxEntries, Long64_t firstentry = 0)

Long64_t Draw(const char* varexp, const char* selection, Option_t* option = "", Long64_t nentries = kMaxEntries, Long64_t firstentry = 0) // *MENU*

void Draw(Option_t* opt)

void Draw(Option_t* option = "")

root [8] TTree::Draw(

You see that the Draw command can take up to 5 arguments but only the first is required, the rest being optional. You can do surprisingly many things from just carefully crafted Draw commands. Try to see if you can plot the difference in the phi coordinate of the first photon (index 0 in the array) and all the charged particles in each event, with the result plotted between 0 and pi (since the largest angle between two vectors is pi).

While analyzing data line by line with Draw commands from the ROOT terminal can get you pretty far, there is a limit to what you can achieve. At some point it's necessary to write code that can do arbitrarily complex logic and cuts. There's quite a few concepts and code that needs to be written to analyze a root file from scratch, however here we're going to take a shortcut and have ROOT auto-generate that for us. At some point it's useful to understand how that works as well but for now we can just use it as a black box that lets us use variables from the file in the code. So to generate the code we open the root file again and use ztree->MakeClass function:

root g.pp-photonHLTFilter-v0-HiForest-tutorial.root

root [0]

Attaching file g.pp-photonHLTFilter-v0-HiForest-tutorial.root as _file0...

(TFile *) 0x268a3e0

root [1] ztree->MakeClass("analysis")

Info in <TTreePlayer::MakeClass>: Files: analysis.h and analysis.C generated from TTree: ztree

(Int_t) 0

root [2]

ROOT created two files for us, analysis.h and analysis.C , which we can start from to analyze the data in the root file. The code in analysis.h is what makes reads in the root file and sets the variables, we can treat this as a black box for now but feel free to try to understand what it does and ask questions about what is happening under the hood.

The first thing we'll do is modify the analysis.C so that we can compile it into an executable. All we need to add is a main() function to satisfy the compiler. So add the following lines to the end of analysis.C :

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

return 0;

}New we can compile and run the code from the terminal:

g++ analysis.C $(root-config --cflags --libs) -Werror -Wall -O2 -o "analysis.exe"

./analysis.exeAt the moment our analysis code didn't do anything, it didn't even open the data file, however if it was able to compile and run it means at that all the root libraries are properly set and configured, which is a good place to start from. Let's also go over what the g++ command does on the first line. It takes the .C file containing the analysis code as input analysis.C . $(root-config --cflags --libs) tells the compiler where to find all the ROOT libraries. -Werror -Wall tells the compiler to treat warnings as errors, this is optional for getting code to run however I recommend keeping it on because it forces you to have cleaner code and helps you find bugs in your code that don't cause the analysis to crash but give incorrect results. O2 is some optimization flag, and lastly -o analysis.exe is the output executable that we will run to do our analysis.

Let's now add a few more lines to analysis.C so that it reads the data and runs the one function that was auto-generated, Loop. Modify the main function in analysis.C so that it looks like this:

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

analysis * ana = new analysis();

ana->Loop();

return 0;

}Compile and run:

g++ analysis.C $(root-config --cflags --libs) -Werror -Wall -O2 -o "analysis.exe"

./analysis.exeThe code still hasn't produced any output, however this time it actually read in the input file and looped through every collision. At this point it's good to review what is a constructor , an instance and a pointer in C++ to understand what happens in the first line analysis * ana = new analysis(); . That's where the file is read in the function analysis::analysis(TTree *tree) defined in analysis.h . The next line calls the Loop function defined in analysis.C which reads each collision in order in the file. The part of the code which loops through all collisions is the following:

for (Long64_t jentry=0; jentry<nentries;jentry++) {

Long64_t ientry = LoadTree(jentry);

if (ientry < 0) break;

nb = fChain->GetEntry(jentry); nbytes += nb;

// if (Cut(ientry) < 0) continue;

}To understand this code you should be familiar with for loops and if statements . The line Long64_t ientry = fChain->GetEntry(jentry); is what loads the jentry'th collision into memory. The way the TTree data structures work in this code is the following, we have the same variables described above, ex. nTrk and trkPt, set for a specific collision . When you call GetEntry(0) it sets the nTrk variable to the number for the first collision, it sets the trkPt array to the momentum of the particles in that collision, and so fourth. When you call GetEntry(1) , it changes the values of all the variables to what they are in the second collision, and so on.

Try to understand how collisions are stored in TTrees here, how we pull all the information one collision event at a time, and how you don't see what's happening in all collisions simultaneously.

Let's make the same plot we did with the TTree::Draw command further up, ztree->Draw("trkPt","trkPt<10 && nTrk>20"), to understand how cuts can be applied when looping through events and looping through tracks.

First we will introduce the cut on the total number of particles in the event by adding a continue statement within the for loop after we do GetEntry to load the collision information.

for (Long64_t jentry=0; jentry<nentries;jentry++) {

Long64_t ientry = LoadTree(jentry);

if (ientry < 0) break;

nb = fChain->GetEntry(jentry); nbytes += nb;

if( nTrk < 21 ) continue;

}Next we'll loop through each of the charged particles within each event. Since there are a total of nTrk charged particles in the event, we will iterate from 0 to nTrk-1 in our trk arrays and check if each track has less than 10 GeV momentum.

for (Long64_t jentry=0; jentry<nentries;jentry++) {

Long64_t ientry = LoadTree(jentry);

if (ientry < 0) break;

nb = fChain->GetEntry(jentry); nbytes += nb;

if( nTrk < 21 ) continue;

for(int itrk = 0 ; itrk < nTrk ; itrk++) {

if(trkPt[itrk]>10) continue;

}

}Lastly we are going to create a histogram, fill in the track momentum for the tracks which pass both of our selections there, and save that histogram into an output file. The code inside will look like this:

if (fChain == 0) return;

TFile * outputfile = new TFile("outfilename.root","recreate");

TH1D * htrkPt = new TH1D("htrkPt","title;xaxis title;yaxis title",100,0.2,10.8);

Long64_t nentries = fChain->GetEntriesFast();

Long64_t nbytes = 0, nb = 0;

for (Long64_t jentry=0; jentry<nentries;jentry++) {

Long64_t ientry = LoadTree(jentry);

if (ientry < 0) break;

nb = fChain->GetEntry(jentry); nbytes += nb;

if( nTrk < 21 ) continue;

for(int itrk = 0 ; itrk < nTrk ; itrk++) {

if(trkPt[itrk]>10) continue;

htrkPt->Fill(trkPt[itrk]);

}

}

outputfile->Write();

outputfile->Close();The lines we added are:

TFile * outputfile = new TFile("outfilename.root","recreate");This creates the output file where our results will be stored.

TH1D * htrkPt = new TH1D("htrkPt","title;xaxis title;yaxis title",100,0.2,10.8);This creates a TH1D histogram object. The first parameter "htrkPt" is the internal name of the histogram, the second parameter defines the visible plot title, x and y axis titles, the third parameter is the number of bins, the 4th and 5th parameters are the min and max x-values of this histogram.

htrkPt->Fill(trkPt[itrk]);This "fills" the histogram, which means it adds 1 to the bin corresponding to this track's momentum. The information this histogram will tell us after it's been filled is the total number of tracks that fall in each of its bins.

outputfile->Write();

outputfile->Close();Lastly these lines write the histogram we have filled to the output file and close the file.

By looking at where the histogram is filled we can see how each of the cuts is applied. Here it's important to understand what the continue statement of C++ does: in a for loop it will skip everything below it and go to the next iteration of the for loop. So in if( nTrk < 21 ) continue; , whenever nTrk is less then 21, the continue statement is executed, and the code below it is skipped, so the histogram is never filled for events having fewer than 21 charged particles. Likewise in the track loop if(trkPt[itrk]>10) continue; , whenever the i'th track has more than 10 GeV trkPt the continue statement is executed and skips to the next track in the track for loop not filling the histogram for those tracks.

With these modifications let's compile, run the code, and open the file the code creates and plot the histogram within it:

g++ analysis.C $(root-config --cflags --libs) -Werror -Wall -O2 -o "analysis.exe"

./analysis.exe

root -l outfilename.root

root [0]

Attaching file outfilename.root as _file0...

(TFile *) 0x32c8cd0

root [1] .ls

TFile** outfilename.root

TFile* outfilename.root

KEY: TH1D htrkPt;1 title

root [2] htrkPt->Draw("pe")

Info in <TCanvas::MakeDefCanvas>: created default TCanvas with name c1

root [3] How does this histogram compare to the one created by the Draw command from before?

This part of the tutorial shows how to fit an invariant mass histogram to measure a particle that doesn't interact direcly with the detector, but decays into particles that we directly measure. First let's run the code.

cd exampleDmeson

. run_macros.shIf you look inside run_macros.sh you'll see it looks for an input file and downloads it if it doesn't exist. Then it runs two macros in root, savehist.C and fitD.C .

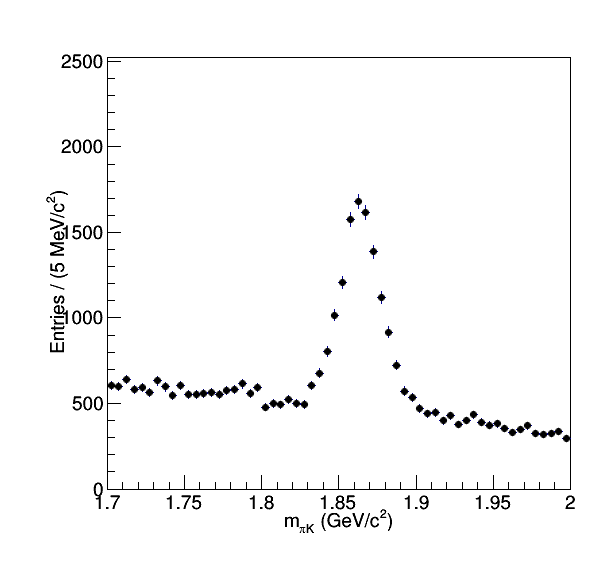

root -b -q "savehist.C+("\"$INPUTDATA\",\"$CUTTRIGGER\",\"$CUT\",\"$OUTPUT\"")"

root -b -q "fitD.C+("\"$OUTPUT\"")"This is another way to run C++ code using root, instead of getting g++ to directly compile the code and then running it, here root compiles the code (the C+ option after the filename does this) and runs it all in one go. The options "-b -q" to root tell it to run in batch mode and quit after running. Whether to compile your code with g++ or root is up to personal preference. The first output this code produces is an invariant mass spectrum. This invariant mass is calculated by taking the sum of momentum 4-vectors for a pair (or more) particles, then calculating the length of that resultant four vector (e^2-p^2). For a random pair of particles calculating the invariant mass in this way will result in a random number, however if the pair of particles happens to be from the same parent particle that decayed, like a D meson, then the value of the invariant mass will be exactly the rest mass of the particle they decayed from. The image below is from taking many pairs of particles and calculating the invariant mass in this way.

We see there is a pedestal coming from picking pair of unrelated particles, and on top of that there is a gaussian-like distribution from when the particles we pick happen to both come from the same D meson decay. In order to count the total number of D mesons we measure in this way we need to take the integral of the region under the peak and subtract from it the combinatorial background from pairs of particles that are unrelated but by chance their invariant mass lies under the peak.

Here fitD.C takes the above distribution as input, defines a functional form that can describe the shape of the full distribution:

TF1* f = new TF1("f","[0]*([7]*exp(-0.5*((x-[1])/[2])**2)/(sqrt(2*3.14159)*[2])+(1-[7])*exp(-0.5*((x-[1])/[8])**2)/(sqrt(2*3.14159)*[8]))+[3]+[4]*x+[5]*x*x+[6]*x*x*x",1.7,2.0);Then guesses some parameters for this function and tells root to fit the function to the histogram by tweaking the parameters until the fit can't get any better. This is a great example of the usefulness of ROOT, since writing a arbitrary function fitter to histograms is a lot of work that ROOT already did for us. Since the function we have fit is a sum of a component which describes the combinatorial background and another component which describes the peak, we can now evaluate how much of the region under the peak comes from D meson decays. Open the output file plots/fitD.pdf to see the result that with the D and background decomposed. Another thing to learn from this macro is how to use the different plotting tools in ROOT, you can see how to manipulate the axis titles, make a plot legend, and making a professional looking plot.

Try to do some of the following tasks which are useful for research both in this group and elsewhere.

- Modify the code we have so far to produce a histogram of the average track momentum distribution that you would see in a typical collision that has at least 20 particles. This is a physically meaningful observable, so it should not depend on any arbitrary decisions we make like the number of events that are in the file or the choice of binning for the histogram.

- Create a new histogram that shows how the mean value of the track momentum (mean of trkPt) changes as a function of the number of tracks in the event.

- Modify the code we wrote so that the cuts we made are not hard-coded in analysis.C , but can be passed in as arguments when we run the code from the terminal. I.e. running

./analysis.exe 20 10will applynTrk>20andtrkPt<10cuts , and changing those cuts just requires changing the parameters you run with,./analysis.exe 30 30for example. - Start using github if you haven't already. Make an account, set up your ssh keys so you can push and pull, fork this repository and start committing and saving your changes.